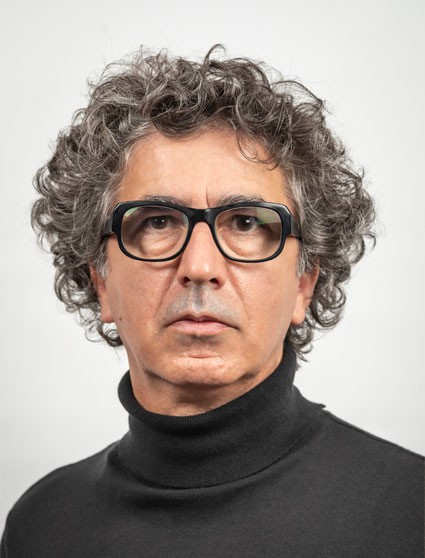

Pedro Portugal

Interview by João Prates

Pedro Portugal was born in Castelo Branco in 1963 and is one of the iconic and multifaceted figures of contemporary Portuguese art. Graduating in painting from the Lisbon School of Fine Arts in 1985, he was one of the founders of the Homeostético movement, along with Pedro Proença, Ivo, Manuel João Vieira, and Xana. This movement challenged established artistic norms, promoting art imbued with irony and social critique. In 2004, the Serralves Museum recognized the group’s relevance with a comprehensive retrospective. Pedro Portugal was also one of the creators of the movements Ases da Paleta, Etno-Estética, Explicadismo, Pandemos, Zuturismo, Arthomem, and KWZero.

His works are part of prestigious public and private collections. A specialist in visual information, Pedro is a painter, sculptor, watercolorist, performer, writer, politician, thinker, farmer, consultant, teacher, researcher, designer, lecturer, and curator, approaching art as a field of constant experimentation and critique. This interview seeks to explore Pedro Portugal’s trajectory, revisiting his most significant phases in the context of the works now published.

When and how did you realize that art was your path?

When my parents took me to Rome at the age of seven, and I saw hundreds of naked men and women in paintings on the walls. When a civilization enjoys living with paintings of naked men and women interacting in different ways and positions in every room of the house, including the children’s bedrooms, it seemed to me at the time a profitable profession. Later, I realized that men and women without clothes didn’t have pubic hair until the late 19th century and that, throughout the centuries, vines and long hair were painted over thousands of pudenda. The same with the smile! There are no depictions of smiles in painting until the late 19th century.

Naked men and women with closed mouths in mythological combinations with hidden pudenda could have been my path! But it wasn’t.

In your opinion, what role did the Homeostético movement play in the artistic landscape of the 1980s? What were you aiming to question?

To question everything, as all artistic movements do, especially those that preceded them. Homeostética is the epitome of the 1980s and also the last group of artists to work together until today. At 23, 24 years old, we divided the world into six continents and created the largest paintings in the history of Portuguese art (200 x 1000 cm). But it’s like those rock bands that have a top hit and then break up with no chance of reunion. In the exhibition 6=0 HOMEOSTÉTICA at Serralves, held in 2003, you can see that zeitgeist in the works, photographs, texts, and manifestos. It’s essentially a graduation show of Fine Arts students made 20 years later in a real museum. To fully understand this fascinating and now-cancelled group of heterosexual male artists, lovers of sex, alcohol, drugs, rock, art, theater, cinema, architecture, and cars, the catalog published by Serralves and the documentary made by Bruno de Almeida explain everything. To further explore that era, I am working on a book featuring thousands of photographs of people I took with the first autofocus cameras at parties and openings: OS8Ø. Artists, collectors, gallerists, critics, and life-enjoyers who frequented galleries and museums at the time. More than half have already passed away.

From the 1990s onward, you began exploring other forms of expression, such as photography, computing, sculpture, and installation. Why did you approach these mediums, and how do you reconcile the idea and the process?

I stopped photographing in 1995. Artists have always sought to use technological innovations for their art, but attribution and meaning differ greatly throughout history. The Greeks didn’t have a word for art or blue. *Techne* was the closest term for art: technique. The color of the sea was something akin to the color of dark wine. Perspective is a technical invention immediately utilized by artists, and then there’s the paint tube, which allowed artists to go outdoors and paint in the countryside, giving rise to Impressionism.

In 1996, you presented the first online exhibition by a Portuguese artist. That year also marked your indirect collaboration with the CPS at the first Portuguese gallery we had in Madrid, Blanca de Navarra. What memories do you hold of that exhibition, and what did it represent for you?

The presentation of the virtual exhibition “Ultimas Pinturas” at Forum Picoas was a commercial failure because, at the time, there were only 80,000 people with internet access in Portugal using 28.8k modems. I gave up on technology because of the infamous obsolescence. Culturgest has a piece of mine from 2001 in its collection that includes software running on Windows 98. The institution keeps a computer from that time to use whenever the work is displayed. Blanca de Navarra was the leading avant-garde gallery in the Iberian Peninsula in the 1990s.

Some of your works are deeply interventionist, such as the "inverted eucalyptus with a luxury car" at the Rotunda do Relógio, the “maintenance circuit” on the stairs of Palácio de São Bento, or the “Alqueva water bottle.” All of these works have ecological concerns. What social and political dimensions do you assign to your work?

Apparently, artistic things placed in public spaces tend to cause turmoil, mostly because of the meanings assigned to them. Planting an eucalyptus tree upside down is politically and socially acceptable, even ecologically, because the tree was sick and becomes a curious object—it looks like a trunk with a nest on top. But painting it orange, parking a luxury car beside it, and placing a large granite plaque reading “MONUMENT TO THE ORANGE STATE” months before legislative elections changes it to something unacceptable, leading to its removal. At a time when Cavaco had promoted eucalyptus as green gold, and articles were published in *Público* and *Expresso,* the then-City Councilor for Tourism of Lisbon, Victor Costa, exploiting the fact that it was part of a program of ephemeral art, had the monument cut down a week later—cowardly, at night. In January 2025, I will install the grand “MONUMENT TO THE PORTUGUESE FOREST” in Lisbon near the Tagus. It will be an eucalyptus tree planted upside down, but this time painted with liquid rubber, like our submarines, and illuminated at night in RAL 3000 red (the color of fire trucks). A sacrificial and iconic monument to the more than 150,000 hectares burned this year. Portugal burns because of laws allowing the four evil queens of the wood and paper industries to dominate the Portuguese landscape. A hectare of eucalyptus can yield up to €20,000 every nine years (double what cork oak yields), making it the most profitable crop. Even burned, it makes money. The four evil queens fund universities, environmental associations, nature protection groups, publications, sponsor TV programs, channels, and RS. Now, benefiting from new carbon credit market legislation, they are preparing to certify their eucalyptus forests (the biggest carbon graveyards) and earn €80 per hectare per year. When the Romans visited 2,000 years ago, they described a forest of chestnut trees all the way to Ericeira. When Napoleon invaded Portugal, records show a desert all the way to the sea… I prefer to look at the planet as James Lovelock or Terence McKenna would, and do nothing in an oak forest the size of Monsanto, 700 meters above sea level, where I live with my wife, a young son, and two white Borzois.

One of the editions presented is based on one of your paintings. How do you see, today, the role of drawing and painting in your artistic practice?

I stopped painting in 1996 with the virtual exhibition “Últimas Pinturas,” but I continue to create series of drawings that I frame with wood from extinct trees. Nowadays, most of the works I produce are made in factories or by artisans.

In "Bananoji," there is an ironic and playful reference to Maurizio Cattelan, and indirectly to Warhol, the Velvet Underground, and Duchamp. How do you interpret this network of references?

Artists create artworks based on the works of other artists. Picasso *picassoed* the entire history of art. "Bananoji" is a linguistic game and a philosophical inquiry into the semantic depletion of symbols in contemporary culture. One of the many ways to make art is to combine two things that have never been juxtaposed inside a museum or gallery: a banana and duct tape. An icon that dethrones 107 years of domination by a ceramic urinal that wasn’t even Duchamp’s. It is the *devenir* marked by Deleuze in the transformation of connections and categories over time.

In 1996, you presented the first online exhibition by a Portuguese artist. That year also marked your indirect collaboration with CPS in the first Portuguese gallery we had in Madrid, Blanca de Navarra. What memories do you have of that exhibition, and what did it represent to you?

The presentation at Forum Picoas of the exhibition – Men and women naked with closed mouths in mythological combinations with hidden privates – could have been my path! But it wasn’t. “Ultimas Pinturas,” the 17th virtual exhibition, was a commercial failure because, at the time, there were only 80,000 people with internet access in Portugal, using 28.8k modems. I gave up on technology because of the infamous obsolescence. Culturgest has one of my works from 2001 in its collection, which includes software that runs on Windows 98. The institution keeps a computer from that time to use whenever the work is exhibited. Blanca de Navarra was the great avant-garde gallery in the Iberian Peninsula in the 90s.

Some of your works are profoundly interventionist, such as the "inverted eucalyptus with luxury car" at the Clock Roundabout, the "maintenance circuit" on the steps of the São Bento Palace, or the "Alqueva water bottle." All with ecological concerns. What is the social and political dimension you attribute to your work?

Apparently, artistic things placed in public spaces tend to cause uproar, mainly due to the meanings attributed to them. Planting an eucalyptus tree with its roots upwards is politically and socially acceptable, even ecologically, because the tree was sick and becomes a curious object – it looks like a trunk with a nest on top. But painting it orange, parking a luxury car beside it, and placing a large granite plaque saying "MONUMENT TO THE ORANGE STATE" a few months before legislative elections changes it from unacceptable to something to be taken down. At a time when Cavaco promoted eucalyptus as green oil, articles appeared in Público and Expresso. The then Tourism Councillor of Lisbon, Victor Costa, taking advantage of it being an ephemeral art program, had the monument removed a week later, cowardly at night. In January 2025, I will install along the Tagus River in Lisbon the grand "MONUMENT TO THE PORTUGUESE FOREST." An eucalyptus tree planted with its roots upwards, this time painted with liquid rubber, like our submarines, and illuminated at night with RAL 3000 red (the color of fire trucks). An iconic and sacrificial monument to the over 150,000 hectares that burned this year. Portugal burns because legislation allows the four evil queens of the wood and paper industries to dominate Portugal's landscape. One hectare of eucalyptus can yield up to €20,000 every nine years (double what cork oak forests yield), making it the most profitable crop. Even burned, they bring profit. The four evil queens fund universities, environmental associations, nature protection groups, publications, sponsor TV programs, channels, RS, and now, benefiting from the new legislation on the carbon credit market, they are preparing to certify their eucalyptus forests (the largest carbon coffin makers) and earn €80 per hectare/year. The Romans, when they visited us 2,000 years ago, described a chestnut forest up to Ericeira. When Napoleon invaded Portugal, records showed a desert up to the sea... I prefer to look at the planet like James Lovelock or Terence McKenna and do nothing in an oak forest the size of Monsanto, at 700 meters altitude, where I live with my wife, a young son, and two white Borzois.

One of the editions presented is based on a painting of yours. How do you see, today, the place of drawing and painting in your artistic practice?

I stopped painting in 1996 with the virtual exhibition "Últimas Pinturas," but I continue to make series of drawings that I frame in wood from extinct trees. Nowadays, most of the works I produce are made in factories or by artisans.

In "Bananoji," there is an ironic and playful reference directly to Maurizio Cattelan and indirectly to Warhol, the Velvet Underground, and Duchamp. How do you interpret this network of references?

Artists create artworks based on the works of other artists. Picasso “picassoed” all of art history. "Bananoji" is a linguistic game and a philosophical inquiry into the semantic void of symbols in contemporary culture. One of the many ways to create art is to combine two things that have never been combined in a museum or gallery: a banana and duct tape. An icon that dethrones 107 years of domination by a ceramic urinal that wasn’t even Duchamp’s. It’s the becoming described by Deleuze in the transformation of nexuses and categories over time.

Art bends when there is an "event" like a urinal turned upside down and called "Fountain," or when a banana is taped to a wall and called "Comedian."

Since the validation of art is certified by galleries and museums, the job of artists today is to convince gallery owners and museum directors to place inside those spaces, which have the magical capacity to transform combinations of objects or things not yet combined – like a urinal into elephant dung or two beer cans on the floor – and gain sanction as art. Beware, this is also the far-right’s argument. Camille Paglia says there is a monolithic orthodoxy in the art world, which isn’t good for art. Everything is sterile, leveled, and with an inflation of mediocrity never seen before. Or as Roger Scruton puts it: The art of the last 100 years is a fraud, an outrageous illusion only fit for the trash. About a year ago, I spoke with one of the biggest collectors in Portugal, who only buys art up to the 18th century. During the conversation, I asked if he had ever tried buying contemporary art. The response was that contemporary artists are only interested in making art to shock the public.

You are critical of the artistic medium and the systems of cultural legitimacy. Your emoji series evokes figures like Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Warhol, and Lichtenstein, combining irony and humor. How do you see humor as a form of subversion?

Art is a very serious thing; it employs many people, and one cannot joke about art. I have a negative sense of humor, and perhaps that’s why it can be interpreted as potentially comical or ironic, to which I am also indifferent. Critical of the artistic medium, yes, and of the systems of cultural legitimacy as well. I have written dozens of articles in newspapers and magazines about it. And yes, I had to invent the State Contemporary Art Acquisition Commission. I negotiated from one million to €300,000 with the stingy Centeno, but now it’s already one million a year. In the two years I was on the jury (during the pandemic), it went terribly, and I was close to resigning. I wrote a text about “My Adventure on the Acquisition Commission,” which includes the resignation letter. To be published later... DGARTES continues to allocate 8% of the budget to visual arts. No Minister of Culture has changed that in the last 50 years. A friend of mine, an employee of the Chiado Museum, never returned to the Museum because he says the Chiado Museum doesn’t exist. I was in a discussion with a former Minister of Culture who believed that DGARTES shouldn’t fund the production of works by artists because artists might sell them afterward... DGARTES funds brushes, paints, and canvases for the artist, and then the scoundrel sells the paintings! There is total visual illiteracy in the political class. There’s only one politician who took a visual arts course, but his opinion of artists is that they are scoundrels: Sérgio Sousa Pinto.

We understand the editions produced by CPS as humanized and collaborative, facilitating access to art. What, in your view, is the social function of graphic art and art multiples?

The social function of art like social housing? There’s the quiet luxury of the super-rich cool, placing a Monet in the bathroom or closet. If one can’t afford a Balenciaga dress, one can buy a scarf or a small accessory. That’s how they make money. CPS members must think about the distance of the investment they make in buying a multiple. At 500 or 5,000 years? If it’s 5,000 years, ceramic or glass works are advisable. Paper can last up to 500 years. There’s no guarantee with colors. LIQUITEX guarantees 50 years, and Rothkos have already started to fade...

We live in troubled times and face great challenges. What role should art play in critical times of social transformation?

In reality, all eras have been troubled and full of challenges. There was a time at the beginning of history when humans spent a lot of time waiting. Inside the cave, waiting for the rain to stop or for spring to arrive. The world was entirely painted, and when they realized that rain and sun erased the paintings, they started painting in dark, hard-to-access caves their favorite animals or those they feared. They were either waiting or painting. For 40,000 years, humans painted millions of creatures until 8,000 years ago, the alphabet was invented. That was the first great extinction of painting. Paintings disappeared from caves and moved to the palaces of kings. From a historical perspective, art has always been linked to power, and since times are always critical and socially transformative,

art and artists continue to play the role they have always had: in the cave waiting for the rain to stop or painting the palaces of kings. Art has always been very expensive to produce.

Assuming the value of art, what do you recommend to the collector members of the Portuguese Printmaking Center?

The assumption of the value of art is extremely variable and the craziest and most unpredictable market for investors. Maurizio Cattelan's banana goes to auction at Sotheby’s for one to one and a half million... If the most famous artist changes every 50 years and art is what remains of civilizations, then they should buy everything and store it in climate-controlled bunkers.